An assortment of short items on various topics, beginning with three from the July 22nd New Yorker. Portmanteaus, New Jerseyization, oology, dago, killer whale, and Gail Collins on Bob Filner.

1. Monster portmanteaus. On p. 25 of the New Yorker, Tad Friend in a Talk of the Town piece about horror moviemaker Roger Corman and his wife Julie:

Lately, the Cormans have been producing films for the Syfy channel. The titles are fairly self-explanatory: “Dinocroc,” “Supergator,” “Piranhaconda.” I balked at “Sharktopus,” Corman said. “I told the network, ‘You should go right up to the acceptable level of insanity in a title, but if you go over it, the audience turns against you’ — and then ‘Sharktopus’ was one of their biggest hits.” Coming soon, therefore, is “Sharktopus vs. Pteracuda” — not to be confused with last week’s succès d’estime “Sharknado,” produced by one of Corman’s many imitators.

From “More dubious portmanteaus”:

The world of portmanteaus is crowded with playful formations that are unlikely to survive for long (Higgsteria), including many that are just for ostentatious display (Piranhaconda and Sharktopus).

2. A prize -ize. On p. 45, in John Seabrook’s “The Beach Builders: Can the Jersey Shore be saved?”:

Orrin Pilkey, a distinguished coastal scientist and author from Duke University, calls the state’s approach to coastal engineering “New Jerseyization.” The term is not complimentary.

I have a sizable file on innovations in -ize, often inside nouns in -ization, including some based on proper names: Gitmo-ize, Cape Codization, Atkinize, Nascarization, Wal-Mart-ization, iPodization, Iraqization, Keplerize, Anderson Cooperization, Vermontize, Politico-ization, Walkenize. In older -ize words, there is a resistance to -izing words ending in vowels and words with accented final syllables, but these constraints are generally lifted for proper-name bases: New Jerseyization, Cape Codization.

3. And an excellent -ology. On p. 52, in Julian Rubinstein’s “Operation Easter: The hunt for illegal egg collectors”:

Oology — the study of eggs — is “one of the most exciting areas or ornithology and, in many respects, one of the least known,” Douglas Russell, the curator of the egg collection at [the Natural History Museum at] Tring [north of London], told me.

Oology is in NOAD2, but I don’t recall having seen this wonderful word before.

4. Another portmanteau. From Thib Guicherd-Callin on Facebook yesterday:

Today is my 12th Ameriversary. (Re-read this word carefully.)

America + anniversary.

5. A slur and a mythetymology. From the NYT on July 23rd, “Barbecue Vendors Ejected From Saratoga Over an Ethnic Slur on Their Food Truck” by Thomas Kaplan:

Andrea Loguidice and Brandon Snooks thought they had won the sandwich lottery when they were awarded a spot to sell barbecue at the Saratoga Race Course this summer. To prepare for the crowds, they developed a special menu, bought a six-foot smoker and cleared their calendar.

But on Friday, opening day at Saratoga, their dream went up in smoke. Complaints came in, not about the cooking, but about the name on the side of the food truck: Wandering Dago, which Ms. Loguidice and Mr. Snooks had thought was cheeky and clever, but which racetrack officials deemed simply offensive. The truck was banned from the grounds.

… Ms. Loguidice and Mr. Snooks, who are both Italian-American, started their food truck about a year ago in Schenectady; their best-seller is the HomeWrecker, which features pulled pork, brisket, smoked bacon, barbecue sauce and melted provolone on a toasted ciabatta roll. She said they meant no offense by using the word “dago,” a slur that the Oxford English Dictionary says is derived from the Spanish name Diego, but which they understood to refer to Italian immigrants who were day laborers, and were paid daily, or as the day goes.

“Our daily pay depends on what happens that day, so we just thought it was a fun play on words,” Ms. Loguidice said. She added: “We didn’t think it was derogatory in any manner. It’s self-referential. Who would self-reference themselves in a derogatory manner?”

Anthony J. Tamburri, dean of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, which is part of the City University of New York, said that regardless of the word’s origin, it was not appropriate for a food truck. He described it as “the most offensive term one could use with regard to an Italian-American.”

An inventive etymology, which removes most of the offense from the word. But it’s a mythetymology, and the word is indubitably offensive. From NOAD2 :

dago noun ( pl. dagos or dagoes ) informal, offensive an Italian, Spanish, or Portuguese-speaking person.

Whether dago is the most offensive term for an Italian-American depends on what you think of wop. From NOAD2:

wop noun informal, offensive a contemptuous term for an Italian or other southern European.

origin uncertain, perhaps from Italian guappo ‘bold, showy,’ from Spanish guapo ‘dandy.’

There’s a mythetymology for this one too, an acronymic one: from WithOut Papers.

6. Killer whales. From the NYT Science Times on July 30th, in “Smart, Social and Erratic in Captivity” by James Gorman:

[Diana Reiss of Hunter College said] she does not see ambiguity about killer whales. “I never felt that we should have orcas in captivity,” she said. “I think morally, as well as scientifically, it’s wrong.”

The animal in question, Orcinus orca, is actually the largest dolphin. Its name apparently came not because it was a vicious whale, but because it preyed on whales.

That would make killer whale a very odd compound, conveyong ‘whale killer’. Wikipedia tells a different, though still somewhat confused, story:

The killer whale (Orcinus orca), also referred to as the orca whale or orca, and less commonly as the blackfish, is a toothed [marine mammal] belonging to the oceanic dolphin family. Killer whales are found in all oceans, from the frigid Arctic and Antarctic regions to tropical seas. Killer whales as a species have a diverse diet, although individual populations often specialize in particular types of prey. Some feed exclusively on fish, while others hunt marine mammals such as sea lions, seals, walruses, and even large whales. (link)

Oceanic dolphins are members of the cetacean family Delphinidae. These marine mammals are related to whales and porpoises. They are found worldwide, mostly in the shallower seas of the continental shelves. As the name implies, these dolphins tend to be found in the open seas, unlike the river dolphins, although a few species such as the Irrawaddy dolphin are coastal or riverine. Six of the larger species in the Delphinidae, [including the killer whale (orca),] … are commonly called whales, rather than dolphins (link)

So killer whales are (in common usage) whales, and some of them hunt (and kill) marine mammals, so killer whale isn’t a bad common name.

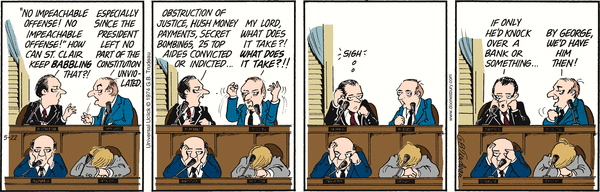

7. A dubious vow. From Gail Collins’s op-ed column in the NYT, “Things to Skip in August”, on the 15th:

You may remember that, in July, Mayor Bob Filner [of San Diego] was charged with sexual harassment by some of his former supporters who claimed that, among other things, he grabbed female workers around the neck and whispered lewd comments in their ears. That was the moment when the nation first became aware of the term “Filner headlock.”

Initially, the information was all secondhand, and Filner vowed that “the facts will vindicate me.” Even then, things looked ominous. For one thing, the facts-vindication defense had been preceded by a vow to behave differently. It was sort of like announcing that you’re innocent but will definitely never do it again.

Definitely an odd sort of speech act.

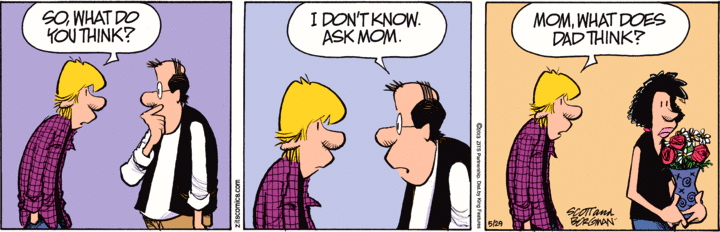

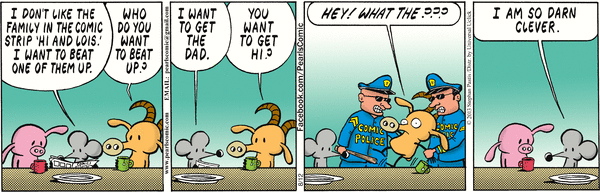

![]()

![]()

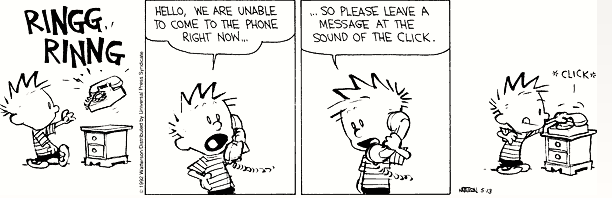

(#1)

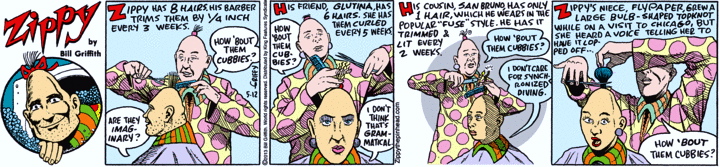

(#1) (#2)

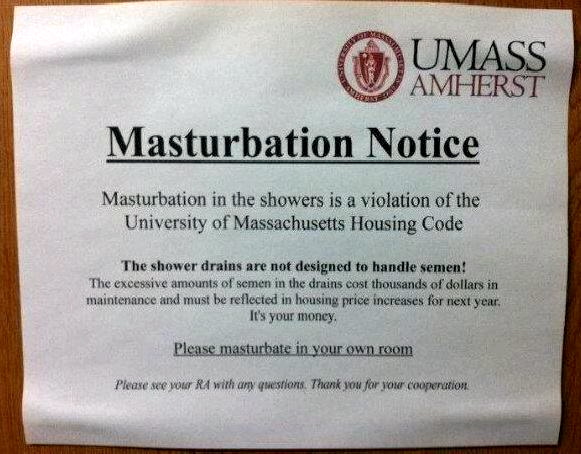

(#2) (#3)

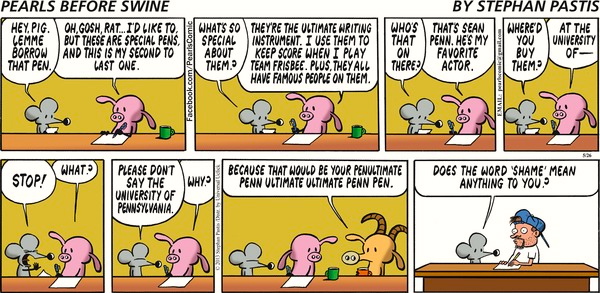

(#3) (#4)

(#4) (#5)

(#5) (#6)

(#6)